Solvig Choi, a volunteer curatorial assistant at Ripon Museum Trust, explores how a female detective in Victorian Britain used forensic linguistic techniques 100 years before the discipline was created. Women police officers have long been overlooked, and a new exhibition opening on 28 April at the Prison & Police Museum will review their place in history and how their role has evolved.

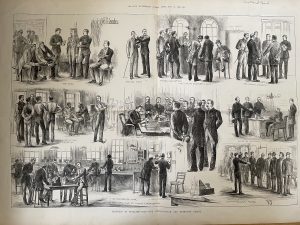

Scotland Yard – Metropolitan and Detective Police. The Illustrated London News. Sept. 29, 1883. From the Ripon Museum Trust collection.

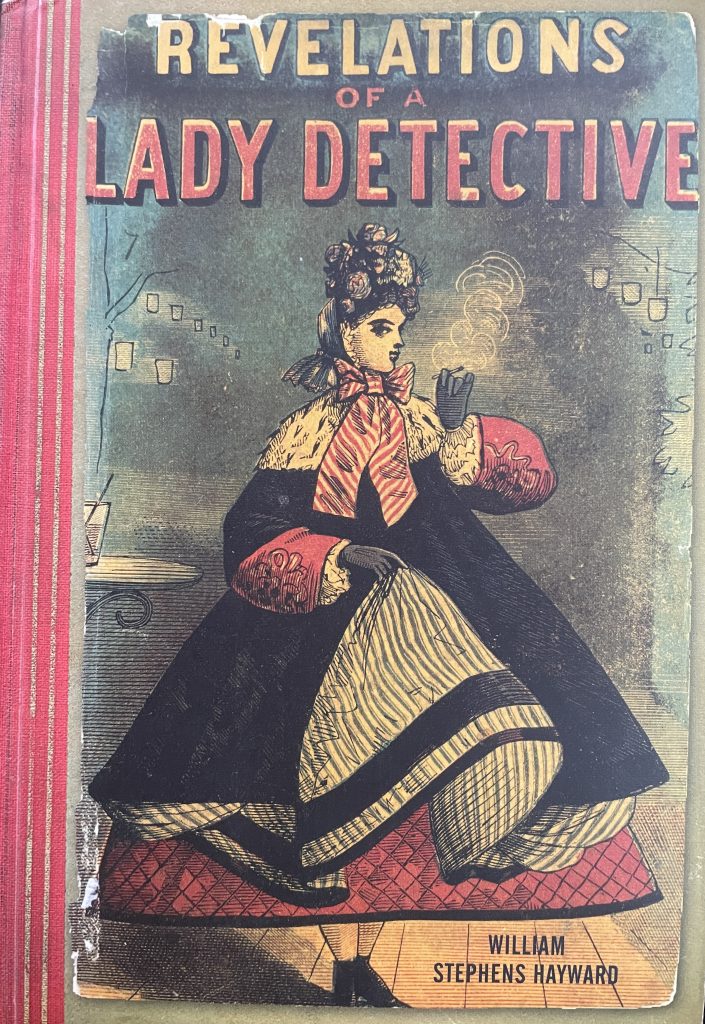

The most well-known Victorian detective is unquestionably Sherlock Holmes—a man as famous for his disfunction as for his being the father of forensics. Women are not even mentioned as police officers in David Taylor’s Crime, Policing and Punishment in England, 1750-1914: women are criminals and prisoners. Taylor says that ‘[t]he dominant gender ideology stressed the importance of the home as the environment in which a woman could fulfil her responsibilities and also be protected from the outside world.’ (p. 60). The cartoon above portrays detectives in Victorian England as men in suits with beards and whiskers. Big skirts, bows, and hats piled high with flowers were not part of the usual image of a police officer, but this identity provided access to places that were out of reach to male detectives in a society where spheres were strictly segregated.

Indeed there is not one but three Victorian novels telling the stories of female detectives: Mrs Paschal in William Hayward’s Revelations of a Lady Detective (1864), Mrs Gladden in Andrew Forester’s The Female Detective (1864) and Miriam Lea in Leonard Merrick’s Mr Bazelgette’s Agent (1888). These female detectives—like Sherlock Holmes—investigated murders, located missing people, unravelled schemes and swindles: skittle sharpers, stolen goods, embezzlement.

In her first case, Mrs Gladden tells the reader the incredible story of a baby bought to commit inheritance fraud. Mrs Gladden used the detailed records maintained by the Victorian bureaucracy to find the identity of the woman who had given birth. She consulted the relieving officer closest to where the baby was sold (a relieving officer kept records of the poor and handed out benefits). She learnt from him that the baby’s mother had died in the workhouse infirmary (where paupers received free medical care). With the main witness deceased, Mrs Gladden transferred her attention to the buyer.

Knowing only that the buyer pronounced ‘th’ as ‘f’ and that she was a ‘real’ lady, Mrs Gladden looked for the houses of ‘gentlemen’. She identified one that ‘consisted of the infant—an heiress, then five years of age—the father, and his sister. I fixed my suspicions immediately upon the latter as the woman who had purchased the child’ (p. 34). Similar to today, Mrs Gladden could not simply go and ask: Did you buy a baby one July night five years ago? Mrs Gladden needed a disguise.

Mrs Gladden chose the identity of a dressmaker and milliner. She even took lessons in sewing and hat-making. In this guise, Mrs Gladden entered the house of her suspect to mend clothes and listen to her target speak:

The uninitiated would be surprised to learn how many ways we have of identification by certain marks, certain ways, certain personal peculiarities—but above all, by the unnumbered modes of speaking, the form of speaking, the subjects spoken of, and above all the impediments or peculiarities of speech…He may change dress, voice, look, appearance, but never his mode of speaking- never his pronunciation. p. 25

Male and female undercover officers. Cartoon. The Police Journal. March 1970. From the Ripon Museum Trust Collection.

Mrs Gladden’s use of pronunciation features to identify a suspect is auditory forensic phonetics. However, it would be 100 years before forensic linguistics became a discipline in the 1960s.

Fiction has long foreshadowed forensic science. Many books detail the forensic methods in Sherlock Holmes, most recently the Science of Sherlock Holmes (2020) by Steward Ross. Forensics textbooks cite male literary detectives: From the Scientific Detective and the Expert Witness (1931) by C. Ainsworth Mitchell, which starts with the fictional male characters who inspired forensic scientists (GK Chesterton’s Father Brown, Dr Austin Freeman’s Thorndyke, Edgar Allen Poe’s Auguste Dupin, and of course Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes), to a History of Forensic Science (2016) by Alison Adam (which talks of Sherlock Holmes and John Thorndyke and the Victorian ‘men of science’). Adam’s book ends with a chapter on literature and discusses how real-life forensic scientists came to emulate art stating ‘it would be difficult to find another scientific discipline where literary characters had quite such an influence on the public imagination and on the scientists themselves’ (p. 184). However, women are not mentioned. Even today we could ask would Miss Marple’s deductions hold the same weight as Sherlock Holmes?

In Agatha Christie’s The Body in the Library, Miss Marple’s astute observations crack the case. Although the detective sees her preoccupation with the dress as trivial and the question of whether fingernails were bitten or trimmed as an annoyance—these are key facts. Christie is famed for her linguistic ability to bury key details (see Catherine Emmott and Marc Alexander in Stylistic Manipulation of the Reader in Contemporary Fiction). However, Mrs Gladden was again proved correct—appearances are easily changed. (And like Mrs Gladden, Miss Marple consulted government family records at Somerset House.)

Fictional female detectives are now common and female forensic scientists lead the way on TV with Dr Sam Ryan in Silent Witness and Dr Temperance Brennan in Bones, both taken seriously by all who encounter them. Women are no longer dismissed as criminals or prisoners.

Mrs Gladden, Mrs Paschal, and Miriam Lea appeared before Sherlock Holmes, and like Sherlock Holmes, they followed clues and gathered evidence with which to identify and prosecute suspects; unlike Sherlock Holmes, they do not inhabit the collective imagination. As such it would be hard to describe Mrs Gladden as the mother of forensic linguistics, even if she did use the same techniques.

Visit our Women in Policing exhibition from 28 April at the Prison & Police Museum, museum tickets are valid for 12 months with unlimited return visits.