Sophie Michell is a postgraduate researcher at the Open University, researching decision-making processes within the coroner’s court.

Murder was a rarity in Victorian Ripon. However, when I was asked to talk about suspicious death in the Liberty, I found three interesting cases.

THE POULTER CASE

The first case concerned the Poulter family. Peter Poulter was born in Marton-le-Moor in 1823, and trained as a shoemaker. He married Mary Stewart in 1868. She was much younger than Peter, born in 1846, and from Penrith. She worked as a gluemaker. In 1876, they moved to Ripon. They lived on Stammergate – now Stonebridgegate – in a courtyard called Grebby (or Grubby)’s Yard.

Their marriage wasn’t a happy one. Peter was an unpredictable and aggressive drunk. In December 1877, he attempted to cut his own throat while drunk. Attempted suicide was a criminal offence, but the magistrates discharged him without charge. He regularly beat his wife. In May 1882, he was bound over to keep the peace after threatening to kill her. He was re-arrested within a day and sent to Ripon Prison for six months.

About six weeks after he was imprisoned, Mary became pregnant. I strongly suspect she resorted to prostitution to support her four young children in the absence of their father – in court, she blamed Peter for her ‘disgrace’ and some years earlier, she had attacked a neighbour for making ‘a scandalous report’. Peter came back from prison in November, by which time Mary’s pregnancy was obvious.

The baby was born in the middle of the night at Easter, which fell at the end of March in 1883. According to Peter, he heard the baby cry, but Mary insisted the baby was born dead. She told him that she’d ‘dealt with it’. None of the neighbours appear to have enquired as to where the baby went, or informed the police.

In October 1883, months after the birth, Peter suffered an attack of conscience. Perhaps this came from guilt, but I think it’s more likely he wanted Mary out of the house. Peter reported the baby’s death to the local constable, who went to investigate. He found the remains of a baby buried under the floor of the coal scuttle, under the stairs. The Poulters were arrested and an inquest was held. The inquest was held on the same day, presided over by Mr Charles Husband, Ripon’s coroner and chief medical officer. However, too many months had passed to be able to tell the baby’s sex, let alone whether it had been born alive or stillborn. This meant there was insufficient evidence to call the baby’s death a murder. Peter and Mary were charged with concealment of birth the next day. The crime of concealment of birth was directly linked to infanticide. Young, unmarried women who were suspected of killing their newborn children were required to prove they hadn’t done it until 1803. In 1803, the law was changed so that the prosecution had to prove the charge. However, criminal juries were not keen to find young women guilty of murder, so the charge of concealment of birth was introduced in 1828. This law allowed the prosecution of any woman who had hidden her pregnancy or birth. Rather than carrying a death sentence, concealment of birth was a crime with a maximum sentence of two years in prison. The new law also allowed anyone who helped a woman conceal a birth to be charged. This is why Peter was also charged, but it was quite rare for men to be charged with concealment. Mary was remanded for trial, and Peter appears to have been bailed.

The trial was held at York County Court on 6th November 1883. Peter’s main crime was keeping silent, although there is some evidence that he was the person who actually buried the body. He was sentenced to one day in prison. Mary was sentenced to three months in York Women’s prison. She appears to have been released in early December.

She did not return to Peter, however. The story has a slightly odd postscript. In 1885, Peter engaged a woman called Emma Forbes to look after their children. Emma ran away with the children! She appears to have been planning to use them to beg. She was captured and sent to prison. Peter died in 1889, and after his death, the children went to live with their mother. As far as I can tell, Mary Poulter died in Ripon in 1930.

This type of suspicious death was not unusual. In 1874, just four people were tried for murder in Yorkshire. One was a woman who claimed her baby had died on the beach at Marske – there was no evidence of foul play, so she was discharged. The second was a man called Will Brown, who had cut his baby’s throat (and his own) while suffering alcoholic delusions in Middlesbrough. Will was found insane, and sent to Broadmoor.

However, the other murders happened one month, and just ten miles apart, close to Ripon. Two women were murdered by family members. The cases had very different outcomes.

THE JACKSON CASE

The first death concerned the Jackson family, farmers who lived in Carthorpe. George Jackson and Ann Ripley married in 1843, and their first son – William – was born the following August. They had seven children in total, and all survived childhood. By 1874, two of their sons were living in the United States, and two others had moved north-east. Their elder daughter, Ann, was living with her husband and baby in Carthorpe. The only children still living at home were Elizabeth, who had just turned sixteen, and thirteen-year-old Anthony. William was in the army, but he was furloughed in April. However, he was not a good houseguest, fighting with his father and drinking to excess. On May 4th, he had a physical fight with his father, and decided to leave the next day. He claimed that he was going to Ripon to find work.

On the 5th, William left home around 5pm. He first visited a neighbour, and then his sister Ann, to say goodbye. Elizabeth met him at Ann’s house and said she would walk a little way with him. Two hours later, they were seen in Kirklington, close to the old mill. Elizabeth was crying, and chasing after William.

Elizabeth was never seen alive again. Her body was found the next morning by a platelayer walking to work, next to the mill race. Her throat had been cut deeply, and her scarf was pulled into the wound. Her dress was around her knees, and there was a pool of blood close by. The nearby stile was covered in bloody handprints. The local constable arranged a search of the area. A razor case, cut into three, was found in the mill race. It was stamped with the insignia of the 77th Foot Regiment. William’s regiment. His pipe was also found in the water.

William was nowhere to be seen.

An inquest was held later that day at the Golden Lion pub in Kirklington. Based on medical evidence that Elizabeth could not have cut her own throat, and William’s property being recovered from the water, the verdict was that Elizabeth was murdered by William.

At first, it was assumed that William had killed himself. However, three days later, on the 9th May, he was apprehended at West Auckland. He was held at Northallerton jail, and moved to Wath on 18th May to be committed for trial. However, on arrival at Wath, he tried to cut his throat with a piece of sharpened zinc that he found on the cell floor. This merely postponed the inevitable. His trial was held at York summer assizes.

On 28th July, William was assigned a defence counsel by the judge. His case was heard on 31st July. His defence was that he hadn’t done it, or if he had, he was mad – he’d suffered a head injury while serving in India. The jury were not convinced, and he was found guilty of murder. The next day, the judge sentenced him to death.

One thing that always surprises me about Victorian justice is how swiftly it occurred. William’s execution was scheduled for 18th August, and he was held in the condemned cell at York. In 1868, public executions were abolished, and William was the first person to be sentenced to death in York since then, so a private scaffold was built on the women’s side of the prison. The night before his death, William confessed to killing ‘Lizzie’. When he confessed, he claimed that he couldn’t remember the murder, but had killed her in a flash of temper because she was annoying him about leaving. I have my doubts about that. Elizabeth was evidently upset about her brother leaving, especially as he was on bad terms with their father. However, she had just broken up with her first serious boyfriend. Perhaps their relationship had already become physical. Elizabeth’s clothes were in disarray, her dress pulled up and soaked in blood at the bottom. Perhaps this was simply a result of dragging her body. Perhaps William wanted to check her virginity, or something more hideous. My colleague Dr Alexa Neale has found evidence that family murderers often try to make the crime scene resemble a sex crime, to avert suspicion, so perhaps this was merely a diversionary tactic. However, the Illustrated Police News reported that there were rumours of William and Elizabeth having an incestuous relationship.

William was executed on 18th August. But this was not the end of the horror of 1874.

THE BARKER CASE

The Barker family came from Kirkby Malzeard, about six miles from Ripon. William Barker had married Anne Bonwell in 1850. William was about forty when they married, and Anne was twenty-seven. They had five children, but two died young. Their surviving children were John William (born in 1851), George and Alfred. They lived together.

However, their house was not happy. William Barker was a violent man, and a renowned miser. He had been jailed for attacking a neighbour in 1864, and was known to beat his wife. This had only become worse since, in 1871, Anne had attempted to leave him. She had taken one hundred pounds of his savings, and then escaped the village with a neighbour, Richard Wood. They were quickly captured, and William took them to court. Anne was acquitted, but Richard was jailed. After this event, William and his sons watched Anne like a hawk, and William encouraged his children to abuse her verbally, and even physically.

John William Barker was a trained butcher, but he was prone to bouts of quinsy, a serious complication of tonsillitis. In February 1874, he was struck with a particularly severe bout, and took a long time to recover. He became strange after he recovered. He wasn’t able to work and became obsessive, mute and intense. He had strange compulsions, to carry meat up and down the stairs before allowing to be cooked. He spent most of his time lying around, reading pulp fiction. At the end of May 1874, he attacked his mother with a belt buckle. His father was sufficiently concerned to enquire about sending John to an asylum. Nothing happened immediately, and John became more violent. He threatened to kill his brother George. George had a job with the Leeds tramway company, and had only been home for the Whitsun weekend. On the 4th June, George was due to travel to Ripon to return to Leeds by train. William decided to go with him as far as Ripon, and to take Alfred with him. John was invited, but refused to go. They left at 9:15am.

Ann was seen outside the house at 9:30am, covered in whitewash. At 11am, a neighbour heard a tremendous row coming from the Barker house. The neighbour’s mother told him to keep out of it. The discord in the Barker household was well known in the village.

William and Alfred returned from Ripon at quarter past five that evening. John was lying in the living room, and calmly informed Alfred that their mother would make tea. He then went to the cellar, and came back within a minute or two. William then came in, and John told him that he had killed his mother in the cellar with a billhook. William sent Alfred, who was only thirteen, to look in the cellar. Sure enough, his mother’s broken body was lying there. A bloody billhook was found on the shelf when the constable examined the scene.

The inquest was held the next day at the Queens Head in Kirkby Malzeard. The evidence suggested that John had gone down to the cellar, where his mother was cleaning the floor, and hacked at her from behind. Ann had two wounds to her head – one on the temple, and one almost severing her head from her body. John then washed his hands, rinsed the billhook and waited for his father to come home.

John was held at Ripon prison. He appeared before the magistrates on 8th June and was committed for full trial. The newspaper reports commented on how well he looked, although he was faint and had to sit during the proceedings. His trial was held at Leeds on 3rd August 1874, just two days after William Jackson was sentenced to death in York. However, unlike William, John had a credible insanity defence.

In the 1840s, a set of rules – The M’Naghten Rules – were adopted for determining whether or not a criminal was insane. The rules were simple. Did the suspect know what they were doing, and did they know what they were doing was wrong? John had a very clear history of being mentally disturbed, triggered by a recent illness, and his behaviour was very strange. His oddness was witnessed by people in the village, and people he worked with, corroborating the family’s assertion of madness. The fact that his father had tried to get him admitted to an asylum was also useful corroborative evidence of madness. Additionally, John’s maternal grandmother had spent time in an asylum – mental illness was considered to be hereditary by the Victorians. John was found not guilty of murder due to insanity.

On 12th October 1874, John was transferred to Broadmoor asylum in Berkshire. He lived at Broadmoor until 1913, when he was sent to Rampton Hospital in Nottinghamshire. Rampton opened in 1912, to relieve the pressure on Broadmoor. John died in Rampton in 1919, having spent forty-five years in secure facilities. His father died in 1890. I wonder whether William Barker regretted his bullying campaign against his wife, or ever linked their erratic and abusive home to John’s insanity.

DIGITISED SOURCES

- Birth, marriage, death and census records, accessed via Ancestry

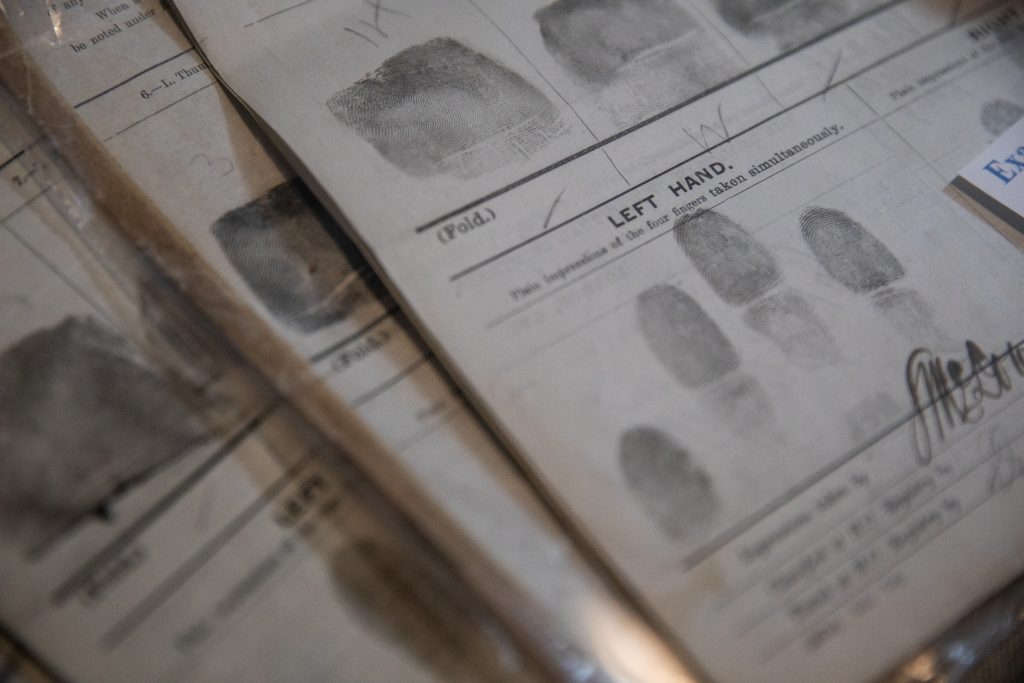

- Criminal Registers, and Calendar of Prisoners, accessed via Ancestry

- Lunacy Patient Admission Records, accessed via Ancestry

NEWSPAPERS: THE POULTER CASE

- York Herald, 1st Mar 1875, p.6.

- Wetherby News, 20th Dec 1877, p.4.

- Richmond and Ripon Chronicle, 13th October 1883, p.4.

- Leeds Mercury, 10 Nov, 1883, p.11.

- Knaresborough Post, 17th Nov 1883, p.8.

- Leeds Mercury, 30th July 1885, p.5.

NEWSPAPERS: THE JACKSON CASE

- Knaresborough Post, 9th May 1874, p.5

- York Herald, 16th May 1874, p.11.

- Illustrated Police News, 23rd May 1874, pp.1-2.

- Knaresborough Post, 23rd May 1874, p.5.

- Knaresborough Post, 6th June 1874, p.4.

- Knaresborough Post, 13th June 1874, p.6.

- Illustrated Police News, 20th June 1874, pp.1-2.

- Knaresborough Post, 1st Aug 1874, p.8.

- Sheffield Independent, 3rd Aug 1874, p.4.

- Knaresborough Post, 22nd Aug 1874, p.5.

NEWSPAPERS: THE BARKER CASE

- Leeds Mercury, 30th March 1864, p.4.

- Leeds Mercury, 15th July 1871, p.8.

- Yorkshire Post, 7th August 1871, p.3.

- York Herald, 6th June 1874, p.6.

- Knaresborough Post, 13th June 1874, p.3.

- Illustrated Police News, 20th June 1874, pp.1-2.

- Yorkshire Post, 10th August 1874, p.3.