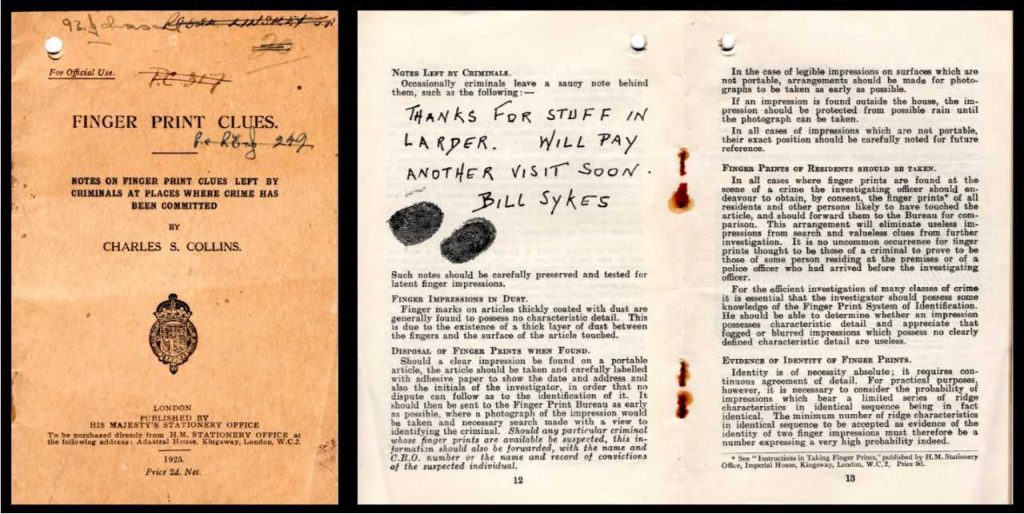

Booklet; Finger Print Clues, 1925

This booklet, entitled ‘Finger Print Clues: Notes on Finger Print Clues Left By Criminals At Places Where Crime Has Been Committed’, was published in 1925 by New Scotland Yard.

The preface of the booklet reads:

“This pamphlet has been prepared for the information of Police who may have occasion to engage in the investigation of crime, and particularly those who possess little or no previous knowledge of finger print identification, in the hope that it may assist them to take full advantage of any finger print clues which may have been left at the scene of a crime”.

The booklet contains information on the nature of finger prints; systems of identification using finger prints; how to search the scene of a crime; how to photograph fingerprints; and how to transport items with fingerprints on them.

What are fingerprints?

Fingerprints are the patterns on the tip of each finger. They are formed by pressure on a baby’s developing fingers in the womb. No two people have been found to have the same fingerprints and Charles Darwin calculated that there is a one in 64 billion chance that your fingerprint will match up exactly with someone else’s.

Fingerprints are made of an arrangement of ridges, called friction ridges. All of the ridges of fingerprints form patterns called loops, whorls or arches. Each ridge contains pores, which are attached to sweat glands under the skin. You leave fingerprints on glasses, tables and just about anything else you touch because of this sweat. These fingerprints are called latent prints. You can also leave visible prints in surfaces such as blood, mud and clay.

Because of their uniqueness, fingerprints can be used to identify someone. The science of using people’s physical characteristics to identify them is known as biometrics. Fingerprints are ideal for this purpose because they are inexpensive to collect and analyse, they are easily accessible, and they never change, even as people get older. Scientists look at the arrangement, shape, size and number of lines in fingerprint patterns to distinguish one from another.

Taking fingerprints

The technique of fingerprinting is known as ‘dactyloscopy’. Until the advent of digital scanning technologies, fingerprinting was done using ink and a card.

To create an ink fingerprint, the person’s finger is first cleaned with alcohol to remove any sweat and dried thoroughly. The person rolls his or her fingertips in ink to cover the entire fingerprint area. Then, each finger is rolled onto prepared cards from one side of

the fingernail to the other. These are called rolled fingerprints. Finally, all fingers of each hand are placed down on the bottom of the card at a 45-degree angle to produce a set of plain (or flat) impressions. These are used to verify the accuracy of the rolled impressions.

Today, digital scanners capture an image of the fingerprint. To create a digital fingerprint, a person places his or her finger on an optical or silicon reader surface and holds it there for a few seconds. The reader converts the information from the scan into digital data patterns. The computer then maps points on the fingerprints and uses those points to search for similar patterns in the database.

Use of fingerprints in Britain

1858 – Official use of fingerprints in Britain was established when Sir William Herschel, an English magistrate working in India, decided to use fingerprinting for contracts with locals and would later go on to put them into a register. Herschel’s idea of fingerprinting was based more on instinct than scientific evidence but it was the first modern use of fingerprinting.

1880 – Dr Faulds, a British surgeon in Tokyo, published his findings that fingerprints could be used to identify people because they are unique, and that printers ink could be used to collect the print. Scotland Yard rejected this work.

1892 – Francis Galton published a book “Fingerprints” in which he detailed the first classification system for fingerprints; he identified three patterns called loop, whorl, and arch. These characteristics are still in use today, often called Galton’s Details.

1892 – Juan Vucetich, an Argentine police official, made the first criminal fingerprint identification. A woman named Rojas had murdered her two sons, then cut her own throat to deflect blame from herself. Rojas left a bloody print on a doorpost. After investigators matched the crime scene print to that of the accused, Rojas confessed.

1896 – Sir Edward Henry, commissioner of the Metropolitan Police of London, created a classification system based on the direction, flow and pattern of the friction ridges in fingerprints. The ‘Henry Classification System’ was used as the primary method of fingerprint classification throughout most of the world.

1901 – Scotland Yard established its first Fingerprint Bureau.

1902 – The following year, fingerprints were presented as evidence for the first time in English courts.

Fingerprinting is a common practice in policing today, and fingerprints can be used as a method of identifying a person regardless of whether they have a criminal record. They also remain intact for some time after death, so they can be used to identify the deceased (along with dental records). Fingerprinting is also used by other organisations for things like security checks, visa applications and even unlocking your smart phone.

You can find out more about fingerprinting at our Prison & Police Museum.

Prison & Police Museum

Prison & Police Museum