Solvig Choi, a volunteer curatorial assistant at Ripon Museums Trust, looks at the place of medical botany in the Victorian era and investigates whether the Ripon Union Workhouse Garden would have been used to grow medicinal herbs for inmates.

A workshop on medicinal herbs will be held at the Workhouse Museum on 15th June 2020, further details will be released soon.

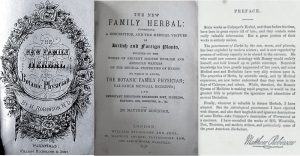

Robinson’s New Family Herbal, Mathew Robinson. Wakefield. 1870

In the Victorian era, medical botany grew in popularity, especially in industrial towns such as Huddersfield, Manchester, and Leeds. Medical botanists were new to a crowded field of physicians, (barber-)surgeons, doctors, apothecaries, and druggists. Medical botanists prescribed herbs and used natural remedies. Barriers to entry were low compared to the medical profession. During this period, medicine became increasingly scientific and barriers to entering the medical profession rose. ‘Orthodox’ medics and ‘fringe’ botanists distrusted each other and fought court cases throughout the period with victories and defeats on both sides.

While West Riding cities and towns such as Leeds, Huddersfield, Wakefield and Skipton all had medical botanists listed in their censuses, Ripon did not. Ripon had physicians, surgeons, doctors, druggists and apothecaries for people with the means to pay. Poor people in Ripon could receive treatment outside the Workhouse under the Old Poor Law. Overseers had some flexibility and were able to pay for treatments using alternative medicine.

The amount spent on medical relief for the poor was low in the North compared to the South, and in the West Riding, it was lower than anywhere in the country. Some say that this was because of ‘the more independent character of the Northern labourer’ or that Northerners had a greater tendency to ‘resort to quack medicine and the druggist’ (Hilary Marland, Medicine and Society in Wakefield and Huddersfield 1780-1870. p. 57). The New Poor Law unsurprisingly was fiercely contested in the North of England. The more ‘independent’ workers hated being forced into a workhouse; the ratepayers loathed the idea of increased costs.

The Ripon Workhouse we see today has only existed since 1854. It was built after pressure from London and twenty years after the New Poor Law was passed. Under the New Poor Law:

‘[W]orkhouses were designed principally for the custardy of the sturdy ne’er-do-well vagrants whose pauper tendencies required to be discouraged; and the necessity of providing for the genuinely sick and feeble was an afterthought…Multitudes of sufferers from chronic diseases, chiefly those of premature age, crowd the so-called ‘infirm’ wards of the houses, and swell the mortality, which is a sad characteristic of these establishments. Examples are not uncommon in which the really able-bodied form but a fourth, a sixth, or even an eighth of the total number of inmates. The fate of the ‘infirm’ inmates of crowded workhouses is pathetic in the extreme. They lead a life which would be like that of a vegetable, were it not that it preserves the doubtful privilege of sensibility to pain and mental misery. They are regarded by officials connected with the establishment as an exceptional but unavoidable nuisance’.

The Lancet Sanitary Commission for Investigating the State of the Infirmaries of Workhouses, 1866.

In Jane Jenkins, Victorian Social Life, British Social History 1815-1914. p. 182

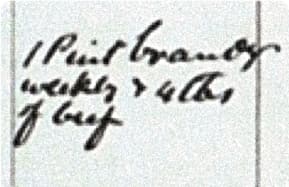

Under the New Poor Law, paupers had to be treated in the Workhouse. A medical officer was appointed and alternative practitioners were excluded. Medical officers were required to hold two qualifications: LSA (Licentiate of the Society of Apothecaries) and MRCS (Member of the Royal College of Surgeons). Medical officers had to pay for medicine themselves so they often prescribed food such as beef and brandy, which were paid for out of the rates, as can be seen in this excerpt from the Ripon Poor Law Union District Medical Relief Book from the North Yorkshire County Records Office.

Ripon Poor Law Union District Medical Relief Book 1861. NYCRO

Records of the exact prescriptions given by workhouse doctors are scarce (Reinarz and Schwarz, Medicine in the Workhouse). Joseph Rogers, a workhouse medical officer in London, did write a diary about his time in the Workhouse. Here he talks of asking the nurse to use a carrot poultice:

‘On going through the wards I ordered what in my judgment was necessary for the sick in the way of medicines, much to the astonishment of the head nurse, who stared at me in a half-dazed manner. There was one patient with a very foul and offensive ulcer, for whom I ordered a charcoal poultice: she came to me before I left the House to ask me “what I meant.” I replied, “A charcoal poultice.” She then said, “I never heard of such a thing before.” I then asked her how long she had been there; she said eight years. The next day I had occasion to order a carrot poultice; I met with the same astonishment and ignorance of what was meant. At last she frankly stated that she was about to learn her duties, for nothing of the kind had ever been used by her before; and further, she said that as she never had any medicine to give the people, she had not troubled herself much about the patients; indeed, I learned on inquiry that she used to be in waiting to see the doctor each morning, and so soon as he was gone she considered her duties were over, and she returned to her own sitting-room till next day. I could never get her to give my medicines as directed’.

(Joseph Rogers, Reminiscences of a Workhouse Medical Officer. pp 114-115)

Rogers was unsuccessful in having medicine used as directed in the workhouse. He did however succeed in reducing the cost of special supplementary diets for the ‘underserving sick’.

The Workhouse Encyclopaedia by Peter Higginbottom gives a general list of medicines used that includes rhubarb powder and oil of peppermint. Although it is possible to grow peppermint and rhubarb in the Workhouse garden, remedies would require additional processing. There is no evidence of either Rhubarb or peppermint being grown or sold to apothecaries to make powders or oils.

The workhouse accounts we have seen do show that the garden was used to grow vegetables such as cabbages. Cabbages, firewood and pigs from the garden were sold and the money received was carefully recorded.

If medical officers were professional doctors, who were the medical botanists? The answer is often working-class men, including shoemakers and cotton spinners (JFC Harrison, Early Victorian Radicals. In Bynum and Porter, Medical Fringe & Medical Orthodoxy 1750 – 1850, p.202). The link between former Chartists and medical botany is discussed by JFC Harrison in a chapter on ‘Early Victorian Radicals and the Medical Fringe’. He notes that the democratic demands of the Chartists for working-class representation in parliament and votes for all men accorded well with the idea of participating in herbal medicine: ‘the people their own medicine’. Former Chartists urged working men to learn how to stay healthy and cure themselves cheaply using herbs (Harrison. Medical Fringe & Medical Orthodoxy 1750 – 1850. p.200).

‘As part of their do-it-yourself appeal, and rejection of elite professionalism, fringe movements tended to disavow the need for any advanced learning. A preference for intuitive and instant forms of knowledge as part of a general anti-authoritarian stance may perhaps be detected here.’ (Harrison. p. 210).

During the Victorian era, the number of garden allotments where the working classes could grow their own produce increased. Although farm labourers in the countryside used allotments to supplement their income, railway workers and miners in towns and cities were reputed gardeners growing amongst other things prize chrysanthemums (FML Thompson, The Rise of Respectable Society. p, 302). It is with some irony that herbal medicine is now embraced by the rich and famous, with women such as Gwyneth Paltrow leading the charge for wellness.

Herbs, however, were not the exclusive preserve of working-class men. Richard Brook, the president of the Huddersfield Naturalist Society (formed with the Earl of Dartmouth as its patron), was a bookseller and printer. He and doctor Mathew Robinson MD in Wakefield published herbal remedy books. Robinson proudly rejected Culpeper’s astrology and Brooks encouraged his readers to learn Latin and Greek terminology.

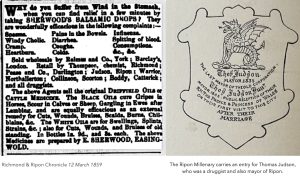

Richmond & Ripon Chronicle 12 March 1859

The Ripon Millenary carries an entry for Thomas Judson, who was a druggist and also mayor of Ripon.

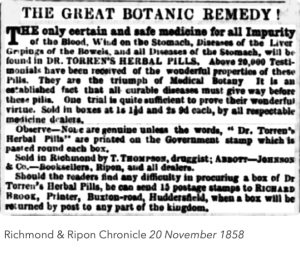

Ripon might not have had medical botanists, but it did have druggists and booksellers. They sold a multitude of ‘quack remedies’, as can be seen from these advertisements in local newspapers. The range of medicines and medical practitioners was bewildering; the outrageousness of promises in proportion to the lack of regulations and oversight. However, druggists were by no means poor or working class. A Ripon druggist, Thomas Judson, was also Mayor of the City and he proudly hosted a reception for the Prince and Princess of Wales on their visit to the city.

Richmond & Ripon Chronicle 20 November 1858

The medical profession would eventually succeed in largely monopolising healthcare. However, herbal medicine has been used throughout the world for millennia and continued to be used throughout the Victorian period by all classes. There is no evidence that herbs were grown in the Ripon Workhouse garden for the use of pauper inmates. Yorkshire families, however, still pass down cures through generations: Children are taught to rub dock leaves on nettle stings and I learnt that my great aunt boiled nettles and put the water on her hair to make it shinier.