Should anyone ever ask me the best way to clean and store a pair of trousers older than me, I will now be able to tell them that they need to start making sausages.

This is because between October and December 2022, I had the opportunity to work on a project with the Ripon Museum Trust, under the supervision of Community Curator Dr Laura Allan. This project was part of my PhD funding scheme supported by the Arts & Humanities Research Council through the White Rose College of the Arts & Humanities, and the hope was that as a history PhD student I could offer some help to the museums and in return learn more about the work of the museum sector.

In her capacity as Community Curator, Laura is involved with a number of exciting projects over the course of the year, many of which (if you are reading this blog) will no doubt be familiar to you. In my three-month stint at the museums, we agreed the best plan would be to help out with the ongoing project of digitisation.

Digitisation means, as the name suggests, creating digital reproductions of objects in the museum collections – photographing and scanning them so that images can be attached to the digital catalogue. This catalogue contains details of every object held by the museum, be it a photograph, a book, or a police helmet – over 4,000 items, of which the majority had yet to be digitised.

My task, then, was to contribute what I could to digitisation, and help Laura to make ready the next step – setting up a publicly-accessible online catalogue that will allow anyone to look at and read about some of the fascinating objects we simply do not have the space to display. This catalogue will generate interest in the collections online and help the amazing objects in the care of the Ripon Museum Trust reach a wider audience, so I was excited to be a part of it.

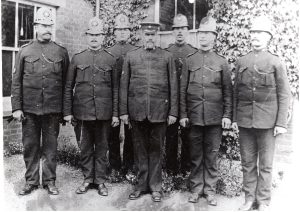

Seven Norfolk constables photographed in an unknown location. From their helmets, the photograph can be dated between 1909 and 1922

There was a lot to learn starting out, and I have to thank Laura as well as volunteer Joyce for familiarising me with the system and the background to the collections. For much of my time, I focused on digitising the photograph collection and document archive – perhaps the objects one most readily associates with digitisation. These are fascinating collections that are not always easy (or even possible) to display in a museum setting, and digitisation will help to make them far more accessible. Photographs and documents have come to the museum from all kinds of sources over the years, and the collections are incredibly varied as a result.

Arthur Edwin Wood of the West Riding Constabulary, 1890s

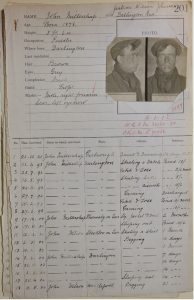

Much of the photograph collection relates to police work – I have digitised photos of police cars, police dogs, police stations, police events, and of course police officers (anything, really, that can follow the word ‘police’), as well as mugshots and crime scene photography. Of course, with photos like this it, is important to be tasteful and respectful, so not all photographs are suitable for digitisation. But when the public catalogue goes live you will be able to browse hundreds of photos relating to the museums’ key themes and the history of the local area.

Sketches of staff at the Detective Training School, Wakefield, signed WJ Miller Nov 1947

The document archive is, if anything, even more varied. As a historian, I might have a natural bias towards documents. But I would hope that anyone can appreciate a collection that ranges from court orders from the seventeenth century to memos about racing pigeons in the Second World War, to ‘cold call’ letters advertising rubber stamps for recording traffic accidents. Besides this are police notebooks and reports, newspapers and clippings, manuals and pamphlets, and several criminal record books.

A page taken from a criminal record book kept in Guisborough. In 1893, John Millerchap was arrested for stealing biscuits

Digitising photos and documents is a fairly straightforward process – box by box, I scanned the items while keeping an eye out for any damage or non-ideal storage conditions, before safely repacking them and returning them to the collections store. Other objects were not so simple.

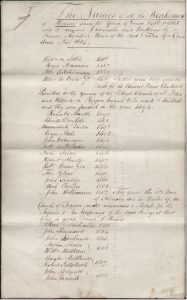

“The Names of all the Weakemen [Wakemen] of Rippon since the yeare of Grace 1486 collected oute of annual Chronacles and Wryttings by Francis Theakstone Maior of the said Towne of Rippon Anno D[omi]ni 1615”

Digitising the uniform collection has been part of an ongoing project for some time now. The museum holds over a thousand items of police uniform (including jackets, trousers, and skirts, but also headwear, fittings, and accessories of all kinds), some over a century old, and by their nature these objects are vulnerable. Unfortunately, in the early days of the Ripon Museum Trust, suitable storage spaces were very hard to come by – before the creation of the current collections store in the workhouse museum, storage was available only in the cellar of the town hall. Aside from being less-than-ideal workspaces for volunteers, cellars are prone to damp, insects, and all manner of dangers to museum objects, especially ones made of fabric.

For this reason, all the uniforms were moved from the town hall cellar to a special quarantine storage space in the museum. From there, on ‘Conservation Tuesdays’, Sonja and John have been taking uniforms one at a time and preparing them for the collections store. Firstly, this means checking each item for damage or problems and giving it a thorough but gentle clean with a specialised museum vacuum and brushes. In the process, we would occasionally find other objects hidden away in pockets (such as gloves, early alcoholometers, and unused first-aid kits). The uniform can then be placed on a mannequin and photographed from multiple angles. Once this is done, the object is carefully packed in an archive quality box and acid-free paper. These boxes and paper are made from inert materials which, unlike many common storage supplies, are as safe as possible for historic material. The uniforms are separated with acid-free paper, with rolled-up ‘sausages’ and ‘nests’ to make sure nothing is squashed too flat, creased, or out of shape.

Leeds City Police jacket, pre-1974. Ribbons above the pockets for ‘Pacific Star, WW2 Star and Police Long Service and Good Conduct 1951’

Since it began, this task has been progressing well, and I was very interested to lend a hand and familiarise myself with the work Sonja, John, and others have been doing. Unfortunately, however, we soon encountered a problem – webbing clothes moths. As the name suggests, these are the moths that are infamous for eating clothes and other fabrics, and they are a nightmare from a conservation perspective. Once they find their way into a box of clothes, many generations of moth can live there, feeding on the fabric. We also encountered, where the old boxes had failed to protect the objects from the damp of the cellar, active mould.

Both of these things can cause major problems in museum collections – if they are not dealt with quickly, the damage can be irreparable. As a result, Conservation Tuesdays took on an emergency importance. Once the mould and pests had been identified, every uniform from the quarantine store had to be checked as soon as possible. The best course of action for mould and pests is to freeze the object for three days at -30°C, so while Laura tracked down a freezer that was up to the task, those of us volunteering on the project checked each and every object individually. The affected items were sealed to prevent further spread while they awaited freezing, while the rest were put to one side to wait out the emergency.

Fortunately, the volunteer community was ready to help, and I have to thank all those who lent a much-needed hand. Between all of us, I am happy to report, we were able to check every item from the quarantine store. Unfortunately, many objects were affected, some of them severely. But with the freezer in place and the problems identified, Laura and the collections volunteers can now work on the solution!

I really enjoyed my time at the Ripon museums. Through working on the digitisation project and assisting with conservation cleaning, I have been able to familiarise myself with a fascinating array of objects – documents, photographs, and uniforms – and learn a huge amount about the world of museums, as well as getting to work alongside the staff and volunteers that keep the whole thing moving. To anyone considering volunteering, I would highly recommend lending a hand in collections.