From the 1880s there was a growing concern about the legal rights of women and children, and a growing opinion that they be treated with justice and dignity. In around 1883 this led to the introduction of police matrons in the Metropolitan Police Force, who at first, were mainly the wives of station sergeants. Their role was to attend to the care and searching of female prisoners, as well as chaperoning female prisoners at the police courts. Later, appointing matrons became more formalised, and they were eventually paid!

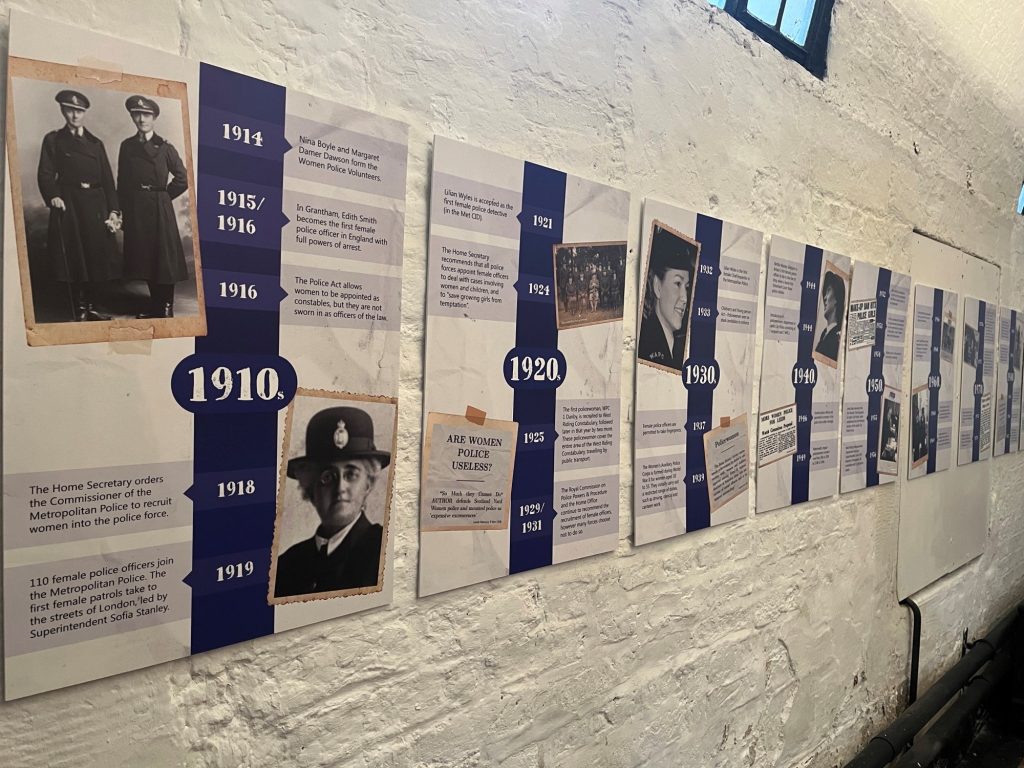

During World War One, two groups were formed with a view to aiding the police, the Women’s Police Service (WPS) and the National Union of Women Workers (NUWW).

The WPS founders had links with the militant suffragette Women’s Social and Political Union, and had an interventionist style, including rescue work, warning young women of the danger of erratic behaviour. They had a uniform and a code of conduct.

The NUWW set up voluntary patrols but distanced themselves from rescue work, positioning themselves more as aides to the established police. Both groups spent a great deal of time policing the behaviour of working-class women, patrolling parks and public spaces, separating courting couples, and moving on “dangerous” women. They did not have the power of arrest.

Following the end of the war, the experiment of Women Patrols was formed in the Metropolitan Police Force, under the control of the Commissioner, and under the supervision of a female superintendent, Mrs Stanley. However, as a result of the cost-cutting Geddes Axe, a few years later the experiment was abolished.

But this was short-lived. In 1923, 50 female officers were resworn (now with full powers of arrest). It was recognised that societal values and behaviours had changed following the war, which contributed to the desire to develop and maintain Women Police. There was a recognition of women as now being a part of public life, for instance, being employed, the wane of the chaperone, women meeting and socialising in cafes without men. However, duties for women police still mainly consisted of dealing with women and children, patrol work, escort duty for juvenile and female prisoners, and hospital duty.

The 1934 Metropolitan Women Police Annual Report said that there were 56 women police officers employed in the force. Their duties described in the report were warnings and arrests for solicitation, finding shelter for stranded persons, and attendance at Juvenile Courts (a result of the Children and Young Persons Act of 1933). Additionally, they acted as matrons at police stations as required. They also undertook plain clothes observation duties in cafes and clubs, and supported raids on brothels. Of 328 arrests made by Metropolitan Women Police Officers in that year, 160 were for soliciting, 81 drunk and incapable or disorderly and 16 for wandering.

In the 1939 Recruitment Booklet for Metropolitan Women Police Officers (It’s Woman’s Work) the duties of Women Police Officers were described as being mainly protective, helpful, and kind.

Following the outbreak of World War Two, the Women’s Auxiliary Police Corps (WAPC), was established to free up men for military duties, with a view to taking on duties that didn’t require full police powers, such as driving and clerical work, and it was only expected to last until the end of the war. However, this war had a similar effect as the previous war, of throwing up social issues in respect of women’s behaviours, as well as the protection of children. Women in the WAPC had duties involving ‘undesirable’ sexual activity, evacuation of children, and arrest of aliens etc.

In 1944 two classes of those in the WAPC were established, those who were doing ’police duties proper’ (including the power of arrest), and those who were doing the more ‘feminine’ duties such as clerical work, and driving. WAPC numbers had grown from 226 at the beginning of the war to 3700 by the end, and in addition there were 400 regular women police officers. The WAPC was disbanded in 1946, but many of the women went on to join regular police forces.

After the end of the war, there was a resistance in some quarters to retain women police, but Miss Denis de Vitre was a strong advocate for their retention and persuaded many Chief Constables to take a wider view of the potential of women police, and to train them with the men. The number of women police in the regular police force grew from 246 in 1939 to 1148 in 1949.

Through the 1950s and 1960s, there was a gradual but patchy shift in the role of policewomen, with some forces moving quicker than others. In 1955 Leeds City Police was the first force to appoint a female Chief Inspector, Jessie Dean. By 1966 there were 4000 policewomen employed in police forces across the country. In 1969 female detectives were working on every type of investigation in every division in the Metropolitan Police Force.

The Equal Pay Act in 1970, and the 1975 Sex Discrimination Act brought some levelling up between male and female police officers. Also, segregation of male and female police officers was abolished. The term Women Police Constable (WPC) was introduced and reinforced equality with male counterparts. The range of duties that women police officers undertook expanded at a faster rate than ever before, and went far beyond the social activities they’d done in the past.

Women police officers were visible on the frontline of demonstrations, they were trained and deployed in the use of firearms, were recruited to CID and undertook investigative work, rose in the ranks to manage and deploy police where situations demanded, such as event management, heading up the National Crime Agency, and more.

Finally in the 1980s they were issued with a truncheon, and a handbag to put it in!

Towards the end of the century significant strides in diversity were being made in all areas of society, and this had a marked impact on the Police and Justice system. In the 1990s women were taking senior roles in a range of spheres, Stella Rimington became head of MI5, Patricia Scotland was the first black woman to become a Queen’s Counsel, in 1992 Barbara Mills became the first female Director of Public Prosecutions, and the first female Chief Constable, Pauline Clare, was appointed in 1995.

Women police officers had strong women advocating for them in the early days, they showed their determination and ability in their valued contribution through two world wars and beyond, they continued to fight for equality with their male colleagues, and undertake the same roles today.

In 2015, Theresa May, then Home Secretary, (at an event celebrating 100 years of Women in Policing), acknowledged the women who had overcome “obstacles, difficulties and resistance, … triumphed over the odds, and won over their male colleagues, demonstrating their professionalism and bravery”.

In March 2021, there were 43762 female officers, over the 43 police forces, making up 32.4% of police officers! In the year April 2020 to March 2021 the North Yorkshire Police force recruited 50 females compared to 38 males.

Visit the Prison & Police Museum where you can further explores the roles of some of the first female police officers to join the force. Has society moved from the segregation of women in policing to full integration or are there still issues to address in modern policing?

References

Open University International Centre for History of Crime, Policing and Justice

British Association for Women in Policing (BAWP)

Theresa May speech 2nd December 2015, British Library

100 years – 100 women